Sendai tansu is the fruit of three craftsmen’s skills

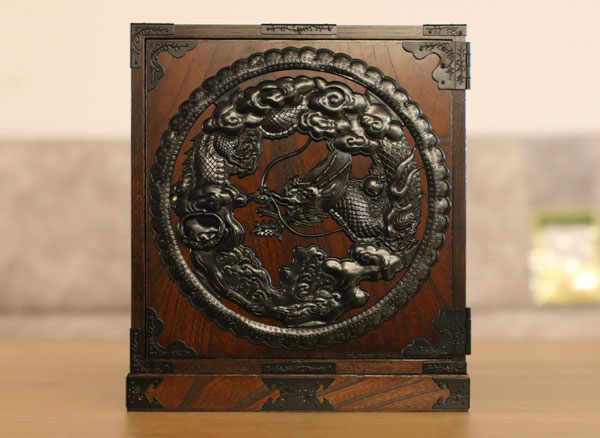

Brilliance That Brings Wood to Life

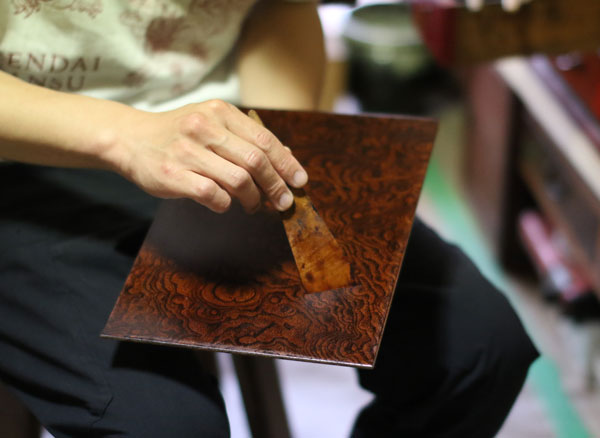

Urushi lacquering gives Sendai Tansu its distinctive shine and refined beauty. A traditional technique called Kijiro-nuri is used to create a deep, mirror-like gloss. Transparent lacquer (suki-urushi) is carefully applied in multiple layers—base coat, middle coat, and top coat—with each layer meticulously polished before the next is applied. This painstaking process enhances the natural grain of the wood and brings out a brilliant, enduring finish.

Craftsman File ①

Lacquer Artisan

Hasebe Urushi Studio

Yoshikatsu Hasebe

I’m the 12th-generation lacquer craftsman in my family. As the eldest son, I always knew lacquerwork was part of my path. But I truly committed to it when I realized during job hunting that a corporate career just wasn’t for me. That’s when I turned back to urushi.

Lacquering styles vary by region. Sendai has its own techniques, and I was encouraged to explore beyond. I studied in Kamakura, Kyoto, and elsewhere—learning carving methods, tools, and even blade shapes from artisans across Japan.

Back then, there wasn’t much interaction between craftsmen. Sendai Tansu developed through division of labor, and we didn’t have the internet or social media to share ideas. I traveled, met people, and absorbed their knowledge through face-to-face exchanges.

These days, I believe we must innovate to keep tradition alive. Making the same item repeatedly may be easier and more polished—but it doesn’t always sell.

Crafts must evolve with changing lifestyles. Sales are what fund future apprentices and keep skills alive. If we want Sendai Tansu to survive, we have to adapt.

Lacquering styles vary by region. Sendai has its own techniques, and I was encouraged to explore beyond. I studied in Kamakura, Kyoto, and elsewhere—learning carving methods, tools, and even blade shapes from artisans across Japan.

Back then, there wasn’t much interaction between craftsmen. Sendai Tansu developed through division of labor, and we didn’t have the internet or social media to share ideas. I traveled, met people, and absorbed their knowledge through face-to-face exchanges.

These days, I believe we must innovate to keep tradition alive. Making the same item repeatedly may be easier and more polished—but it doesn’t always sell.

Crafts must evolve with changing lifestyles. Sales are what fund future apprentices and keep skills alive. If we want Sendai Tansu to survive, we have to adapt.

Craftsman File ②

Lacquer Artisan

Kuri Kōbō

Hideki Kuriya

Originally, I wasn’t a lacquerer—I just liked making things. When I started thinking seriously about craftsmanship, Sendai Tansu was the most accessible. I could work and learn at the same time, so I dove in.

I began lacquering at age 34. It wasn’t particularly difficult—I simply knew I had to learn. I was lucky: a friend introduced me to a professor of urushi arts at Tohoku University of Art & Design. I commuted to Yamagata for about a year to study with him. That experience became the foundation of my Kijiro-nuri work today.

If anything was challenging, it was the lack of community. There weren’t many specialists around to talk to or learn from.

Lacquering is simple in theory—you apply, then polish. But getting it right is tricky. If the technique is off, the lacquer turns dark and hides the grain. Making the wood shine through is the hard part, and it took years of trial and error.

Sendai Tansu began in the late Edo period and evolved through the Meiji export boom. It’s a living tradition that must keep evolving. If we only cling to the old ways, we lose relevance. Of course, division of labor makes change harder—but I believe in innovation, even in small steps.

I began lacquering at age 34. It wasn’t particularly difficult—I simply knew I had to learn. I was lucky: a friend introduced me to a professor of urushi arts at Tohoku University of Art & Design. I commuted to Yamagata for about a year to study with him. That experience became the foundation of my Kijiro-nuri work today.

If anything was challenging, it was the lack of community. There weren’t many specialists around to talk to or learn from.

Lacquering is simple in theory—you apply, then polish. But getting it right is tricky. If the technique is off, the lacquer turns dark and hides the grain. Making the wood shine through is the hard part, and it took years of trial and error.

Sendai Tansu began in the late Edo period and evolved through the Meiji export boom. It’s a living tradition that must keep evolving. If we only cling to the old ways, we lose relevance. Of course, division of labor makes change harder—but I believe in innovation, even in small steps.

Craftsman File ③

Lacquer Artisan

President of Chōshirō

Yūki Kanno

Why I Chose the Path of a Craftsman

There are three key moments that led me to become a craftsman—each was love at first sight.

The five-storied pagoda of Jogi-san Saiho-ji Temple in my hometown, the elegant metalwork of Kikumasu, the awe-inspiring Todai-ji Temple, and my encounter with Sendai Tansu. Each of them left a lasting impression and stirred something within me.

At first, I aspired to become a temple carpenter. I was simply drawn to the idea of craftsmanship itself. I remember the moment I saw the pagoda at Jogi-san—I was struck by how magnificent it was and thought, “I want to be part of something like this.” That was the spark that ignited my passion for making things.

Later on, at a vocational training school, I met a senior apprentice of Master Hasebe, who introduced me to Sendai Tansu. One day, he received a request to repair a tansu, and I happened to be present. Witnessing the meticulous work firsthand left a deep impact on me. I immediately said, “I want to do this,” without hesitation.

From there, I trained under Master Hasebe and eventually went independent in April 2024. Today, in a twist of fate, I’ve even had the opportunity to work on the restoration of the very same pagoda that first inspired me.

Master Hasebe had a philosophy of respecting tradition while also embracing modern techniques. I was deeply moved by this balanced approach, and I hope to continue creating with that same spirit—honoring the past while remaining open to innovation.

Reflections on My Apprenticeship

Looking back, I don’t recall my training period as particularly difficult.

Master Hasebe was the kind of teacher who would give you ten answers when you asked just one question. Rather than being strict, he was kind, generous, and passionate. I found great joy in lacquer work and took the initiative to ask questions and learn directly through hands-on experience.

What I Value in My Work

After going independent, there were times when work temporarily dried up. During those periods, I revisited what I had learned from my master, especially modern techniques, and began to re-examine the value of Sendai Tansu from my own perspective.

To me, craftsmanship is not just about good materials—it’s about understanding the origin and background of each piece. Who made it, and why? I believe the true value lies in that story. That’s why I make a point of researching the historical and cultural context before expressing it through meaningful form.

I currently serve as a vocational school instructor, helping to pass down skills to the next generation. Sendai Tansu emerged from the cultural history of the Sendai Domain during the late Edo period. I believe it is my responsibility to communicate not just the techniques but the historical backdrop that gave rise to them.

Thoughts on the Future of Sendai Tansu

Mr. Yaegashi, the metal fittings craftsman for Sendai Tansu, currently has no apprentices. The continuation of this craft is becoming increasingly difficult. Still, I don’t believe that preserving a tradition means copying it exactly as it was. We also need people who can shape tradition into forms that resonate with the present day.

When I create tansu, I listen carefully to the client’s hopes, preferences, and budget. While respecting the origins and history of Sendai Tansu, I craft each piece with care and thoughtfulness.

It may sound extreme, but I believe that as long as a piece carries meaning and spirit, even if its shape evolves, it can still rightfully be called “Sendai Tansu.”

As times change and new needs emerge, I want to respond to those changes without losing sight of the essence. My goal is to carry the tradition of Sendai Tansu into the future, preserving its soul while allowing it to grow.

There are three key moments that led me to become a craftsman—each was love at first sight.

The five-storied pagoda of Jogi-san Saiho-ji Temple in my hometown, the elegant metalwork of Kikumasu, the awe-inspiring Todai-ji Temple, and my encounter with Sendai Tansu. Each of them left a lasting impression and stirred something within me.

At first, I aspired to become a temple carpenter. I was simply drawn to the idea of craftsmanship itself. I remember the moment I saw the pagoda at Jogi-san—I was struck by how magnificent it was and thought, “I want to be part of something like this.” That was the spark that ignited my passion for making things.

Later on, at a vocational training school, I met a senior apprentice of Master Hasebe, who introduced me to Sendai Tansu. One day, he received a request to repair a tansu, and I happened to be present. Witnessing the meticulous work firsthand left a deep impact on me. I immediately said, “I want to do this,” without hesitation.

From there, I trained under Master Hasebe and eventually went independent in April 2024. Today, in a twist of fate, I’ve even had the opportunity to work on the restoration of the very same pagoda that first inspired me.

Master Hasebe had a philosophy of respecting tradition while also embracing modern techniques. I was deeply moved by this balanced approach, and I hope to continue creating with that same spirit—honoring the past while remaining open to innovation.

Reflections on My Apprenticeship

Looking back, I don’t recall my training period as particularly difficult.

Master Hasebe was the kind of teacher who would give you ten answers when you asked just one question. Rather than being strict, he was kind, generous, and passionate. I found great joy in lacquer work and took the initiative to ask questions and learn directly through hands-on experience.

What I Value in My Work

After going independent, there were times when work temporarily dried up. During those periods, I revisited what I had learned from my master, especially modern techniques, and began to re-examine the value of Sendai Tansu from my own perspective.

To me, craftsmanship is not just about good materials—it’s about understanding the origin and background of each piece. Who made it, and why? I believe the true value lies in that story. That’s why I make a point of researching the historical and cultural context before expressing it through meaningful form.

I currently serve as a vocational school instructor, helping to pass down skills to the next generation. Sendai Tansu emerged from the cultural history of the Sendai Domain during the late Edo period. I believe it is my responsibility to communicate not just the techniques but the historical backdrop that gave rise to them.

Thoughts on the Future of Sendai Tansu

Mr. Yaegashi, the metal fittings craftsman for Sendai Tansu, currently has no apprentices. The continuation of this craft is becoming increasingly difficult. Still, I don’t believe that preserving a tradition means copying it exactly as it was. We also need people who can shape tradition into forms that resonate with the present day.

When I create tansu, I listen carefully to the client’s hopes, preferences, and budget. While respecting the origins and history of Sendai Tansu, I craft each piece with care and thoughtfulness.

It may sound extreme, but I believe that as long as a piece carries meaning and spirit, even if its shape evolves, it can still rightfully be called “Sendai Tansu.”

As times change and new needs emerge, I want to respond to those changes without losing sight of the essence. My goal is to carry the tradition of Sendai Tansu into the future, preserving its soul while allowing it to grow.