Sendai tansu is the fruit of three craftsmen’s skills

Decorative Metal That Brings Elegance and Strength

On top of the brilliant urushi lacquer, it’s the decorative metal fittings that give Sendai Tansu its signature flair. These fittings are crafted from iron sheets, then hand-hammered with motifs like dynamic dragons, graceful peonies, and powerful guardian lions (karajishi). Each one breathes life into the tansu.

Some chests contain over 200 individual fittings—both large and small—all of which reinforce the tansu’s strength and durability. With their intricate forms and bold relief, these metalworks are the artistic soul of Sendai Tansu.

Some chests contain over 200 individual fittings—both large and small—all of which reinforce the tansu’s strength and durability. With their intricate forms and bold relief, these metalworks are the artistic soul of Sendai Tansu.

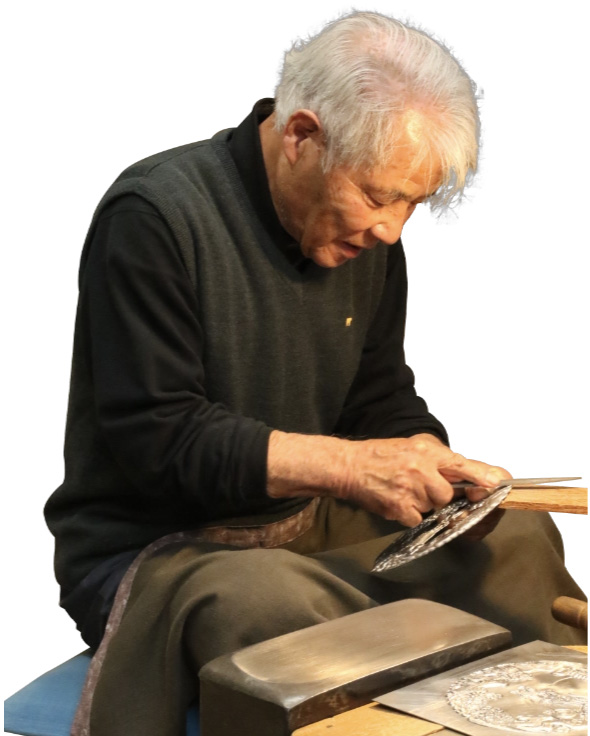

Craftsman File ①

Kanagu Artisan

Yaegashi Sendai Tansu Hardware Workshop

Eikichi Yaegashi

“My story begins around age 20. I didn’t go to high school—just straight into work after junior high. My first job was at a hotel restaurant in Sendai. During a renovation break, I went home for a few days—and that’s when my father suggested, ‘Why not try this job? I think it suits you.’

At first, I didn’t take it seriously. But he brought it up again. Looking back now, if he hadn’t said anything, I probably wouldn’t have returned. A couple of months later, I left the hotel job and started working in the family business.

Oddly enough, my time washing dishes at the hotel turned out to be helpful. It taught me hierarchy, discipline, and work ethic—things that carried over into this job. About a year in, my father praised my work. That really stuck with me. Back then, it was rare for master craftsmen to offer praise.

From that point on, I started enjoying the work. I never thought about returning to Tokyo. I wanted to go independent eventually, but some things prevented that. So I stayed.

Today, I make sure to stamp every piece I create with my name. It’s a mark of pride—and a promise. I never cut corners, even when money is tight. In fact, having my name on every piece probably keeps me honest.

I come from a family of nine children. Five boys—and four of us became kanagu artisans. It’s almost unheard of now. We were rivals in a sense. Even my older brother was a competitor.

Lately, I’ve been hoping to take on an apprentice. But financially, it’s tough. That’s one of the hardest parts right now. The tools we use aren’t mass-produced—you have to make or modify most of them yourself. That costs time and money. If I give my apprentice tools, I can’t work. If I can’t work, I lose jobs. It’s a delicate balance.

My father told me it would take ten years to become a full-fledged craftsman. For me, it took twelve. We don’t mass-produce parts here—everything is custom made. That means I can’t say, ‘I can’t do it.’ I’m a craftsman. I have to make it work.

The problem these days is that even if someone trains to become a craftsman, many give up before they’ve really started. Teaching and learning—it’s hard on both sides. But I still hope to pass this craft on to the next generation.”

At first, I didn’t take it seriously. But he brought it up again. Looking back now, if he hadn’t said anything, I probably wouldn’t have returned. A couple of months later, I left the hotel job and started working in the family business.

Oddly enough, my time washing dishes at the hotel turned out to be helpful. It taught me hierarchy, discipline, and work ethic—things that carried over into this job. About a year in, my father praised my work. That really stuck with me. Back then, it was rare for master craftsmen to offer praise.

From that point on, I started enjoying the work. I never thought about returning to Tokyo. I wanted to go independent eventually, but some things prevented that. So I stayed.

Today, I make sure to stamp every piece I create with my name. It’s a mark of pride—and a promise. I never cut corners, even when money is tight. In fact, having my name on every piece probably keeps me honest.

I come from a family of nine children. Five boys—and four of us became kanagu artisans. It’s almost unheard of now. We were rivals in a sense. Even my older brother was a competitor.

Lately, I’ve been hoping to take on an apprentice. But financially, it’s tough. That’s one of the hardest parts right now. The tools we use aren’t mass-produced—you have to make or modify most of them yourself. That costs time and money. If I give my apprentice tools, I can’t work. If I can’t work, I lose jobs. It’s a delicate balance.

My father told me it would take ten years to become a full-fledged craftsman. For me, it took twelve. We don’t mass-produce parts here—everything is custom made. That means I can’t say, ‘I can’t do it.’ I’m a craftsman. I have to make it work.

The problem these days is that even if someone trains to become a craftsman, many give up before they’ve really started. Teaching and learning—it’s hard on both sides. But I still hope to pass this craft on to the next generation.”